Chimel vs california case brief – The Chimel v. California case brief, a landmark Supreme Court ruling, delves into the intricacies of warrantless searches and the Fourth Amendment’s protections against unreasonable searches and seizures. This case established a two-prong test that guides law enforcement officers in determining the validity of warrantless searches, shaping modern policing practices.

The Fourth Amendment safeguards individuals from unwarranted government intrusions, but the “exigent circumstances” exception allows for warrantless searches in urgent situations. The Chimel test balances these competing interests, ensuring that searches are conducted reasonably and with proper justification.

Chimel v. California Case Overview

The Chimel v. California case, decided by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1969, established important limits on the scope of warrantless searches conducted by law enforcement officers.

The case arose from the arrest of Theodore Chimel, who was suspected of robbery. After arresting Chimel in his home, the police searched the entire house, including drawers and closets, without obtaining a warrant. The search yielded several items that were later used as evidence against Chimel at trial.

Chimel challenged the legality of the search, arguing that it violated his Fourth Amendment right against unreasonable searches and seizures. The Supreme Court agreed with Chimel, ruling that the warrantless search of his home was unconstitutional.

Court’s Reasoning

The Court held that the Fourth Amendment requires law enforcement officers to obtain a warrant before conducting a search of a person’s home, unless there are exigent circumstances that justify a warrantless search.

The Court reasoned that the home is a place where people have a reasonable expectation of privacy, and that warrantless searches of the home are presumptively unreasonable.

The Court also noted that the warrant requirement serves several important purposes, including:

- Preventing arbitrary and oppressive searches

- Ensuring that searches are conducted in a reasonable manner

- Providing a record of the search

Exceptions to the Warrant Requirement

The Court recognized that there are some exceptions to the warrant requirement, such as:

- Searches incident to arrest

- Searches of vehicles

- Searches of open fields

- Searches based on probable cause and exigent circumstances

However, the Court emphasized that these exceptions are narrowly tailored and that law enforcement officers must have a valid reason for conducting a warrantless search.

Fourth Amendment and Warrantless Searches

The Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution protects individuals from unreasonable searches and seizures. It requires law enforcement officers to obtain a warrant based on probable cause before conducting a search or seizure. However, there are certain exceptions to this warrant requirement, one of which is the “exigent circumstances” exception.

Exigent Circumstances Exception

The exigent circumstances exception allows law enforcement officers to conduct a warrantless search or seizure if they reasonably believe that there is an immediate threat to life or property. This exception was applied in the case of Chimel v. California.

In Chimel, police officers had probable cause to believe that Chimel was committing a crime in his home. They entered his home without a warrant and arrested him. The Supreme Court held that the warrantless entry was justified under the exigent circumstances exception because the officers reasonably believed that Chimel was about to destroy evidence.

Chimel Test for Warrantless Searches

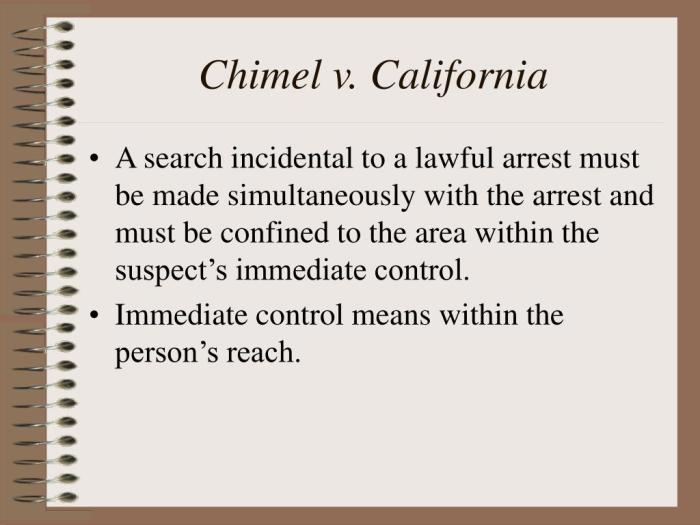

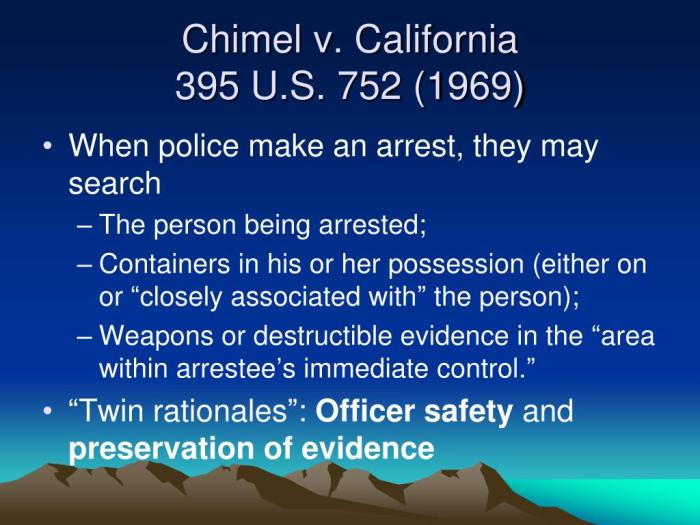

The Chimel test, established in the 1969 case of Chimel v. California, provides a two-pronged framework for determining the validity of warrantless searches.

The first prong requires that the search be incident to a lawful arrest. This means that the search must be conducted contemporaneously with the arrest and must be limited to the area within the arrestee’s immediate control, known as the “wingspan rule.”

The second prong requires that the search be necessary to prevent the destruction of evidence or to protect the arresting officers from harm.

Examples Meeting the Chimel Test

- A search of a suspect’s pockets immediately after being arrested for a traffic violation.

- A search of a suspect’s car after being arrested for drunk driving.

Examples Failing the Chimel Test

- A search of a suspect’s home several hours after being arrested for a misdemeanor.

- A search of a suspect’s vehicle after being arrested for a non-violent crime.

Exceptions to the Chimel Test

The Chimel test is a strict standard that limits warrantless searches incident to arrest to the arrestee’s person and the area within his immediate control. However, there are a few exceptions to this rule that allow law enforcement to conduct warrantless searches beyond these limits.

Searches Incident to Arrest

One exception to the Chimel test is searches incident to arrest. This exception allows law enforcement to search the person arrested and the area within his immediate control for weapons or evidence that could be used against him.

The rationale behind this exception is that it is necessary to protect law enforcement officers and prevent the arrestee from destroying evidence. For example, if a person is arrested for robbery, the police may search him for a weapon that could be used to harm the officer or to escape.

Consent Searches

Another exception to the Chimel test is consent searches. This exception allows law enforcement to search a person or place with the consent of the person who has the authority to consent.

The Chimel v. California case brief explores the limits of warrantless searches incident to an arrest. In lesson 1 Truman and Eisenhower , we delve into the domestic and foreign policy challenges faced by these two presidents. Returning to Chimel v.

California, the Court held that a search incident to an arrest must be limited to the arrestee’s person and the area within his immediate control.

The rationale behind this exception is that a person has the right to consent to a search of his or her property. For example, if a person is arrested for driving under the influence of alcohol, the police may ask the person to consent to a blood test to determine his or her blood alcohol content.

Impact of Chimel on Law Enforcement Practices

The Chimel decision had a profound impact on law enforcement practices. Prior to Chimel, police officers had broad discretion to search incident to arrest, often conducting extensive searches of the entire premises where the arrest occurred. However, Chimel limited the scope of warrantless searches incident to arrest to the area within the arrestee’s immediate control.

This limitation has significantly constrained the ability of police officers to conduct searches incident to arrest. Officers must now carefully consider the scope of the search and ensure that it is limited to the area within the arrestee’s immediate control.

This has led to a decrease in the number of warrantless searches incident to arrest and has helped to protect the privacy rights of individuals.

Development of Search Incident to Arrest Exception, Chimel vs california case brief

In response to the Chimel decision, the Supreme Court developed the search incident to arrest exception. This exception allows police officers to conduct a warrantless search of the area within the arrestee’s immediate control if they have probable cause to believe that the search will produce evidence of the crime for which the arrest was made.

The search incident to arrest exception has been narrowly construed by the courts. In order to justify a search incident to arrest, the police must show that the search was conducted within the arrestee’s immediate control and that they had probable cause to believe that the search would produce evidence of the crime for which the arrest was made.

Legal Precedents and Subsequent Cases: Chimel Vs California Case Brief

The Chimel decision was influenced by several legal precedents and has subsequently been cited and applied in numerous cases.

Legal Precedents

One of the most significant legal precedents for Chimel was Weeks v. United States(1914), which established the exclusionary rule. The exclusionary rule prohibits the use of evidence obtained through an illegal search or seizure in criminal trials. This rule helped to shape the Chimel Court’s analysis of the Fourth Amendment and its holding that warrantless searches are presumptively unreasonable.

Subsequent Cases

The Chimel test has been cited and applied in numerous subsequent cases, including:

- Maryland v. Buie(1990): The Court held that the Chimel test applies to searches of vehicles.

- Arizona v. Gant(2009): The Court held that the Chimel test does not apply to searches of the passenger compartment of a vehicle if the police have probable cause to believe that the vehicle contains evidence of a crime.

- Utah v. Strieff(2016): The Court held that the Chimel test does not apply to searches of cell phones.

These cases have helped to clarify the scope and application of the Chimel test.

Clarifying Questions

What is the Chimel test?

The Chimel test is a two-prong test used to determine the validity of warrantless searches. It requires that the search be incident to a lawful arrest and that there be probable cause to believe that the search will yield evidence of the crime for which the arrest was made.

What are the exceptions to the Chimel test?

There are several exceptions to the Chimel test, including searches incident to arrest, consent searches, and searches of vehicles.

How has the Chimel decision impacted law enforcement practices?

The Chimel decision has had a significant impact on law enforcement practices. It has led to a decrease in the number of warrantless searches conducted by police officers and has made it more difficult for prosecutors to obtain evidence in criminal cases.